Peacemakers Belong in the Courts, Too

A few days ago I was asked to give a short talk to a small group of dedicated men and women, most of them in their 20s and 30s, who were doing a training session in mediation.? These people were working with Inafa? Maolek, a conflict resolution group that has been active on Guam for 29 years now under its guiding spirit, Pat Wolff. ?These good people?peacemakers by avocation?take their skills where they can use them. They work with couples experiencing trouble in their marriage, neighbors who have run-ins with one another, schools in which sparks fly between different ethnic groups or rival gangs.They do great work wherever they are allowed in?but, as I told them in my talk, this just isn?t good enough.? You see, they?re on the scene doing their best before the cops are called in.? But once the police siren sounds and the handcuffs are slammed on, their work ends.

Pat told us that this?wasn’t?always the case.? Some years ago, the public prosecutor and her assistant, both Guamanian women, welcomed mediators from groups like Inafa? Maolek as an alternative to formal court proceedings. If the problem could be resolved without a formal trial, and if restitution was made and the parties went away satisfied that justice was done, why go through the formal trial process?? The victim gets restitution, the offender gets another chance, and sometimes the offender and the victim may even part on good terms.? What?s not to like about that?

Yet, when the Guamanian women were named judges and their positions occupied by others, some of the court officials who replaced them complained that to bring the offender and the victim together in a person-to-person meeting was to ?revictimize the victims.?? So Inafa? Maolek was shut out of such criminal cases, all of which were left to the government to prosecute. The incident was no longer viewed as Juan vs. the storeowner who caught him shoplifting. It was elevated to Juan vs. the Territory of Guam.? Somehow, the victim was overlooked except as a witness for the prosecution.

Things didn?t always work this way on Guam.? Once upon a time, as one of the mediators reminded us, the village commissioners settled most of the disputes within the village and cop cars were rarely seen in the neighborhood. ?Disputes? or ?misdeeds? that would be classified as crimes today were usually taken care of in the typical Micronesian method. The commissioner might talk to the parents of both parties and request their help in working out a resolution to the problem.? Other islands might not have had commissioners, but chiefs or pastors or respected elders would have played the same role.

Commissioners, of course, don?t have the same authority in Guam they once did.? For one thing, villages have become heterogenous with a mix of Chamorros, Filipinos, statesiders, and perhaps some Chuukese or Pohnpeians thrown in. Our ?communities? are personal, now recorded on the list of contacts in our cellphones.? Even so, there must be something we can do to improve on the present system.

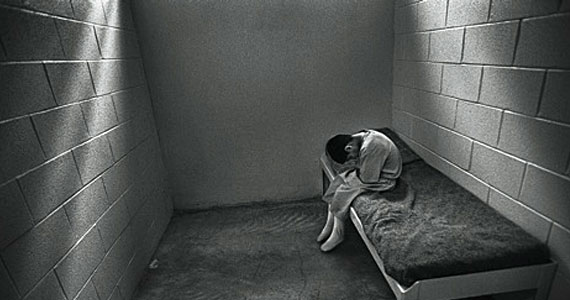

Not so long ago I was told that Guam, with a population of about 150,000, has over 500 people currently in prison. Chuuk, with a population of 50,000, may have about 30 or so in jail.? What that means is that Guam has a prison rate six times higher than Chuuk (or Pohnpei, for that matter). Is Guam really six times more troubled than Chuuk?? Or is it the same problem as in the US these days?an imprisonment epidemic run wild?

I vote to let Inafa? Maolek into the court system to do their restorative justice work in place of a trial whenever possible.? Let these folks try to do what the commissioners once did on the island. Who knows, maybe there?s still a chance to get Guam?s prison rate down to something approaching Chuuk’s.