Let?s Hear It For Shame I: The Shame Game

“Let’s Hear it for Shame,” a Five Part Series

At the risk of sounding like the old fogey that I am (80 years old, after all), I offer my thoughts on the passing of a key social tool. ?Let?s Hear It For Shame? is the title of this five-part series.

I: The Shame Game

This is the first segment of that series on shame, with all that it means today and meant in the past.

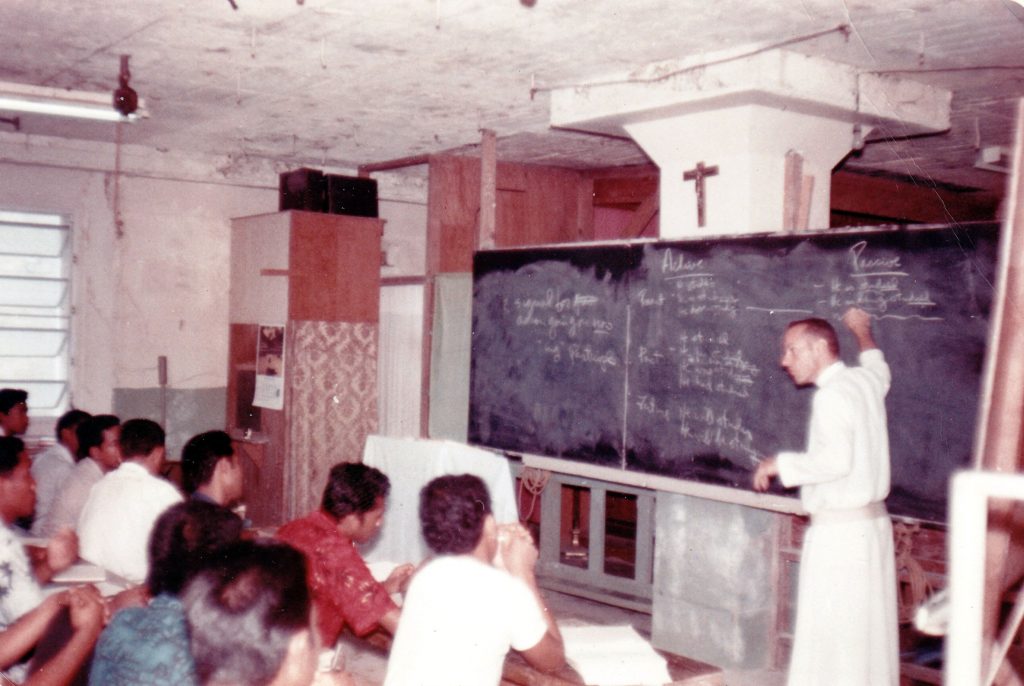

I was giving the keynote presentation at a Pacific education conference when something I said drew a gasp from the audience. I had just said that a second grade teacher of mine had scolded me for habitually writing the number 7 backwards. She called me up to the board and had me fill half the blackboard with 7’s written the right way while my classmates snickered. ?Was I ashamed that day?? I asked rhetorically. ?Sure,? I admitted, ?but the shame didn?t kill my self-confidence or traumatize me.?

I wanted to make the point that ?shaming? has become a dirty word in our day. But it is also a useful tool?one that worked with me seventy years ago. Even more, it is a tool that is especially effective in the Pacific. What really seemed to shock the listeners, though, was my encouragement to use this tool without apology, as generations of Pacific educators have done.

The educators seemed horrified by this advice. Shaming kids? Doing so in front of other kids? How could a teacher be so callous toward the feelings of young children!

Meanwhile, I was astonished at the hypersensitivity to the use of shame that had evidently developed over the years in the Pacific as in America. Did these island teachers know that a few decades earlier their parents were proudly recounting their experiences under Japanese teachers: kneeling in the corner with arms outstretched, having a pencil painfully entwined in their fingers, being slapped on the head or back. The island parents I knew back then expressed their earnest hope that American teachers would have the guts to use similar methods to discipline the younger generation.

I did my best as a Jesuit scholastic at Xavier High School in Chuuk to carry out their wishes. Sometimes it was a drumbeat on the shoulders of an unruly student, but it might also be a sarcastic comment as I flipped a poorly done assignment to the floor. Even today students still remind me of the ?25-cent or 50-cent stamps? on the back they received on their back when I lapped them during our afternoon physical fitness. Do I detect a certain pride in their voice as we reminisce about such things?

But all that was long ago.

These days shame has clearly come into disrepute. Social media, while advertising the horror of shame, has helped make us acutely conscious of all its various manifestations: body shaming, food shaming, weight shaming, ethnic shaming and whatever other type there might be. The original purpose, however well-intentioned, is disregarded if the effect is to bring a blush to the face of the victim.

Parents have been known to charge into the principal?s office to denounce a teacher?s shaming of their child, even if its purpose was to keep their child in line or to drive him to success in his classwork. Or they may react to the benching of their child in a basketball game as a shaming device, thus suggesting that the feelings of their child should come before the good of the team.

Have young people become so acutely sensitive these days that it would be impossible for them to endure what their elders would have tolerated without a murmur?