Don?t Believe Everything You Read about Jesuits

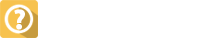

Fr. Diego Luis San Vitores, a Jesuit like the pope (and myself), has become something of a fascination here on Guam these days. His claim to fame is that he first brought the faith to the Marianas in the late 1600s. In fact, he was the first missionary to reach any of the Pacific islands. Nowadays little cards with a portrait of the man and a prayer for his canonization can be found everywhere on the island. There are relics on the altar that people venerate after mass, and even an old black habit that was said to have once belonged to him among the museum holdings.

For the past couple of months I?ve been busy doing my own little part in the campaign for his canonization. Why not? It offers me a wonderful opportunity to do what we tried to do for all those years at MicSem?explore the boundaries of faith and culture. Not only that, but the work is like being back at my old MicSem desk. I?m writing a long monograph on the life and times of the man, and we?re also preparing a half-hour video documentary on San Vitores.

It?s a fascinating, and badly misunderstood period of island history filled with ironies. A man who is an apostle of peace inaugurates the off-and-on ?Spanish Chamorro Wars? that run for 30 years. But mulling over the old documents once again can bring surprises. For one thing, the military garrison that accompanied San Vitores to the Marianas was made up of about 20 Filipinos, some of them as young as 12 years old. Even the adults in the group could handle farming tools a lot more easily than they could fire a musket. They were supposed to train the people, docile and easily converted (the Jesuits thought), in useful trades, although they also picked up their muskets and machetes in time of danger to serve as a militia.

I took the trouble of doing a body count of Chamorros and Spaniards during the 30-year period of the so-called wars, partly because I was hoping to finally lay to rest the old argument that the muskets were responsible for the depopulation of the Marianas. It does seem to be a matter of historical record that the Chamorro population dropped from 40,000 to 4,000 over that period of time. But the body count in the documents I looked through, including detailed reports for each year, was surprisingly low. An average of four or five local people a year were killed in hostilities, while the Spanish mission party was losing two a year.

This doesn?t add up to nearly enough to explain the drastic loss of people during those years. But the population of Kosrae took a similar nosedive during the 19th century during the whaling era. Ships bring Westerners with all kinds of diseases for which local people have not built up an immunity. So perhaps the Spanish did kill all those people after all, but unintentionally through germs rather than with guns. What nailed the case for me was in reading about a four-year period during which 920 people on Guam died, but only 20 of them were killed in battle. Presumably the rest simply caught one of the epidemics that was making the rounds?the ?disease of the ships,? as they were called.

The lesson is not that Jesuit missionaries are harmless (my old basketball buddies and former students know better than that). The lesson is that things are not always what they seem to be, so don?t believe everything you read in history books (including mine).