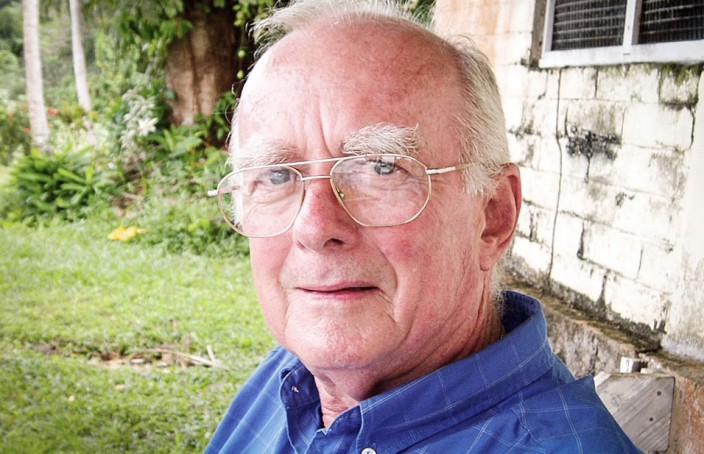

Paul Horgan: A Man of Quiet Dedication, A Friend of All

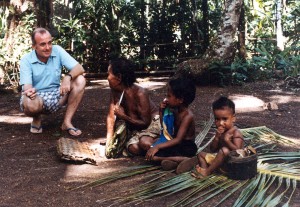

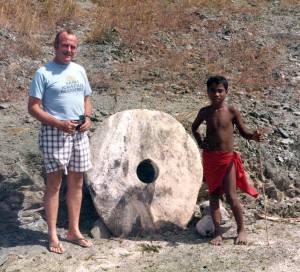

Paul spent much of his adult life in Yap doing parish ministry, but with so little fanfare that many Yapese wouldn?t have been able to tell you much more about him other than that he was a priest. He was quiet, something of a church mouse, unless he was riled. But if you made friends with him, you had a friend for life. For most of his life he smoked a pipe. Sometimes the only way you could tell he was around was the curl of pipe smoke from his room.

Even so, Paul had a good sense of humor. In my first year at Xavier, at a time when I still knew nothing about the islands, Paul offered me what he said was a treat–a tiny red plant that I still could not identify as a chili pepper. As soon as I popped it into my mouth, my face must have turned luminous red with?smoke coming?out of my nose and ears. Paul stopped laughing long enough to offer me another tiny green treat. ?This,? he told me, ?will relieve the heat.? I believed him and tossed it down, entirely unaware that hot peppers came in two different colors.

His own eating habits were remarkable, I soon learned. One of his favorite snacks was peanut butter and pickle sandwiches, sometimes sprinkled with cheese. Wherever he lived, the refrigerator was always stocked with the raw materials he needed for those strange delights he managed to concoct.

Paul Horgan was born in New Jersey, but he took the train across the river each day to attend Xavier High School when it was still renowned as the Jesuit military school in New York. I always had difficulty imagining him in a military uniform, but the same could be said about others who attended that school, became Jesuits, and later served in the islands–Bill McGarry, Joe Cavanagh, and Jack Curran, among others.

We entered the Jesuits a year apart and did our novitiate in different places, but we met in philosophy a year before he was assigned to the Caroline and Marshall Islands. Paul and I had a few things in common: we were both the oldest of five boys in the family, and we both had lost our mother when we were young. When I followed Paul to the islands a year later, our friendship was sealed.

After Paul returned to the islands following ordination, he worked at Xavier for a few years as personal secretary for Bishop Kennally. When the bishop retired, Paul was sent to Yap where be began a long stint as parish priest. He did nothing flashy, began no new programs, wrote no books. That wasn?t his style. But he served with distinction because he was seen to be dedicated to his people. He adopted Yap, and I don?t think it?s an overstatement to say that Yap adopted Paul.

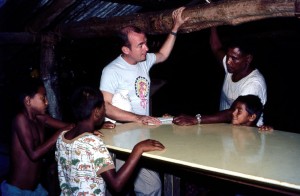

In later years Paul was assigned to PATS, the Jesuit vocational school on Pohnpei, where he taught and counseled, served as chaplain and cared for the infirmary. A Jesuit Volunteer working at the school at the time recalled how immensely popular Paul was among the students. When the students chose guidance counselors, well over 80 percent of the student body would ask for Fr. Horgan. As busy as he was with the infirmary and other responsibilities, he would spend a great deal of time meeting with students and getting to know them, tracking their studies, monitoring their development. Somehow he also managed to pack students into the daily masses at PATS, and was always there with a prepared homily and his notes on a 3×5 index card. The volunteer added that those masses were a special time for him, and he felt that they were for the students as well. Apart from his contributions to the school itself, Paul was a strong source of personal support for the school staff, Jesuit and lay. But all of this was done in his own quiet way: no drama, no awards received, no self-promotion. He was just taking care of his friends–but it seemed that almost everyone was his friend. No wonder the staff took special delight in celebrating his birthday each year with the cake and ice cream they knew he would enjoy.

Paul was sent back to the US in 2010, although he would have gladly stayed on in the islands. About a year after his return to the mainland he suffered a stroke. It happened in the middle of the night and he was not found until eight hours later when another Jesuit entered his room and found him lying on the floor. He underwent therapy for a time to learn to walk once again and to regain his speech since half his mouth had been paralyzed. I would visit him from time to time, occasionally with an old friend of his who was eager to see how he was doing. But Paul was never a battler. After we had finished updating him on what we were doing, he might speak a couple of sentences–but would invariably signal that he had come to the limit of his powers by drawing his good hand over his lips in a slicing motion.

In time he could no longer even get out those two or three sentences. His strength, or perhaps his will, failed him, and he lapsed into silence for the last two years of his life. He who had once enjoyed classical music settled into watching daytime TV shows. Whatever happened to my playful friend from the past, I used to wonder as I watched him sit motionless in his wheelchair with his eyes on the screen. Did he ever get lost in the past, as I did, and dream of the old days when he was saying two or three masses on Sunday and had pastoral responsibility for half of Yap? Was he ever reliving his time in the classroom and campus ministry office at PATS? Was he even aware of the impact that he had on the lives of so many–those students at Xavier and PATS, and the parishioners on Yap?

He died as he lived–quietly, and with a prayer on his lips (I like to think) for those islanders he served for so long and whom he still longed to serve. They surely miss him, and so do I.