San Vitores: Hero or Villain?

Stand outside the new Guam museum and read what’s inscribed on the wall: “Before these (Spanish) people arrived, we didn’t know rats, flies, mosquitoes… and disease.” Just to underscore that point, there are the statues of the chiefs (Hurao and Aguarin) who resisted the foreigners, those despoilers of this land.

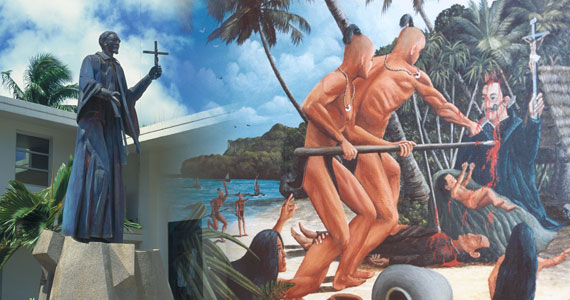

Cross the street and catch the Sunday mass at the cathedral, with its own array of statues, its spirited singing, and its faithful followers. This all started, of course, with Diego Luis de San Vitores and his companions, who came to share their faith with the people of these islands.

So, were Blessed Diego and his party “despoilers of the land” first and foremost? Or do we see them as benefactors who brought the religion that has practically defined the island for over three centuries, even if other nasty things, including deadly plagues and violence, were add-ons?

What do we think of San Vitores, the individual who brought the Spanish to Guam to stay? Is he a hero or a villain? Should we honor him for bringing the faith? Or revile him for destroying the culture?

Are the people singing hymns in the cathedral at odds with those pumping their fists as they read what’s inscribed on the walls of the museum? Are there two different mindsets about all this? Is this cultural schizophrenia?

The rats and mosquitoes and diseases were real, even if they weren’t intentional–and the damage they did is beyond dispute. Then there were the fights that led to loss of life (although not nearly as many deaths as the early historians imagined).

The island people suffered at that time as the population plummeted. People were lost in great numbers. But what about the culture? Was the integrity of the culture destroyed? Are today’s Guamanians cultural orphans?

Only if you’re identifying culture with spears carved out of thighbones of the dead, or village clubhouses for young men. How about the man nginge’, or techa, or respect for the dead, or veneration of the spirits? Not only do they survive, but they are embodied in the religion that San Vitores and his party introduced to the island long ago.

Even so, these questions may be a battleground for determining who Guamanians are as a people. Some might stand with the radical chiefs (the ones celebrated on the walls of the new Guam Museum) who saw the newcomers as a destructive force. But there were other chiefs (at least five of them) who picked the other side and stood by the missionaries when they were under attack. Was this a matter of principle, or just a replay of old simmering quarrels within the island community?

So, the islanders in the past may have been as divided on this issue as we are today. In the end, though, they bowed to the inevitable and worked together to stitch together a new life for themselves–a life that would have traditional elements woven into the new village life. Eventually they decided it was futile to have to choose sides.

The results seem to have worked out pretty well so far, most of us would agree. Shouldn’t we reach the same conclusion they did?